Have you noticed an unusual swelling on your beloved canine companion's face or neck? It could be more than just a simple bump; it might be a sign of salivary gland cancer, a rare but aggressive disease that demands immediate veterinary attention.

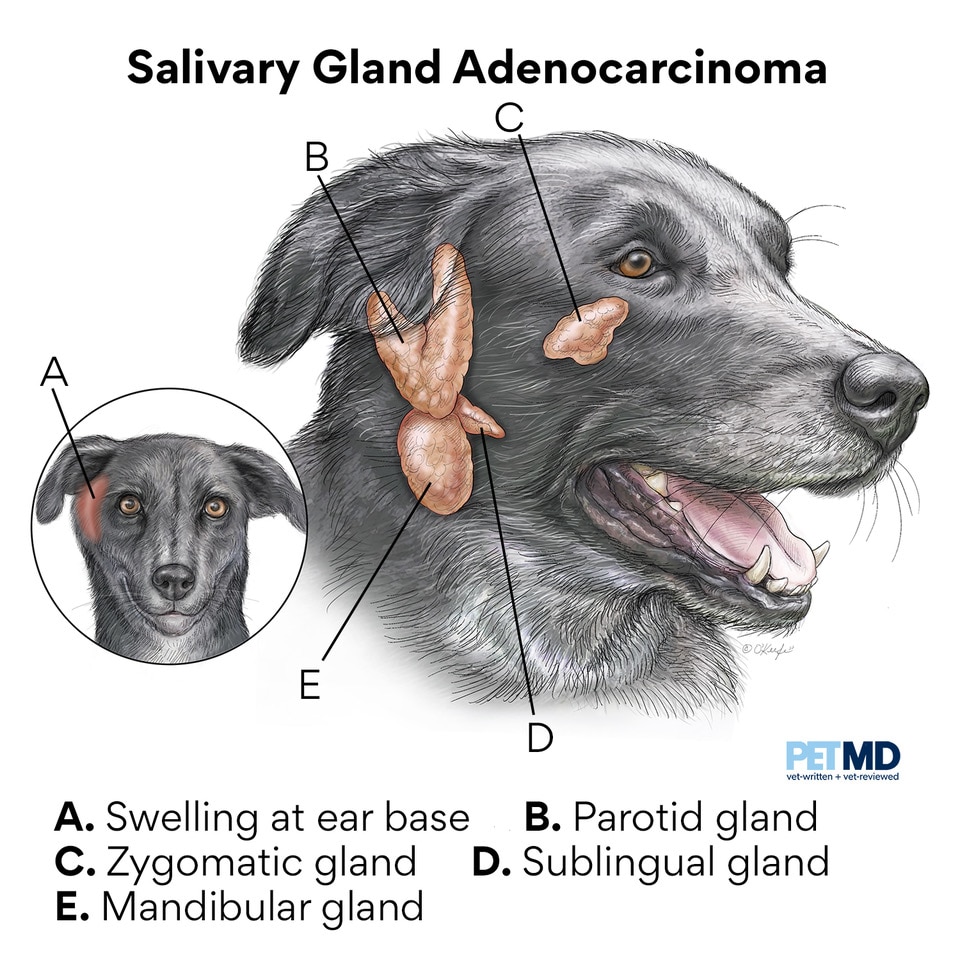

Salivary gland cancer in dogs, though uncommon, is a serious concern for pet owners. These tumors develop within the salivary tissues, and while many salivary gland swellings are benign, some can be malignant. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent type of salivary gland cancer found in dogs, known for its aggressive nature and potential to spread. These tumors originate from the salivary glands, including the parotid, mandibular, sublingual, and zygomatic glands. Early detection and intervention are crucial for improving a dog's prognosis.

| Category | Information |

|---|---|

| Name | Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs |

| Description | A rare and aggressive neoplasm originating from the salivary glands. |

| Common Type | Adenocarcinoma |

| Affected Species | Dogs (primarily older patients, 10-12 years) |

| Predisposition | No specific breed or sex predilection |

| Location of Glands | Parotid (near the ear), Mandibular (under the jaw), Sublingual (under the tongue), Zygomatic (near the eye) |

| Symptoms | Drooling, difficulty eating/swallowing, facial swelling, weight loss, lethargy |

| Diagnosis | Physical examinations, imaging (CT scans, MRIs), biopsy |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy |

| Prognosis | Depends on stage at diagnosis and effectiveness of treatment |

| Related Conditions | Salivary mucocele (sialocele), sialadenosis, infection, inflammation |

| Rarity | Uncommon in dogs (0.09% incidence) |

| Epithelial Origin | Majority (88.8%) of neoplasms are of epithelial origin |

| Reference | American College of Veterinary Surgeons |

The salivary glands themselves are exocrine glands responsible for producing saliva, which aids in digestion and keeps the mouth moist. Dogs possess four main pairs of these glands: the mandibular glands located under the jaw, the parotid glands near the ear, the sublingual glands under the tongue, and the zygomatic glands near the eye. Any of these glands can potentially develop tumors, highlighting the importance of regular check-ups and vigilant observation by owners.

While primary salivary gland cancer is rare in both dogs and cats, it's crucial to recognize the signs. Owners often notice a mass or swelling as the initial symptom. Other signs can include drooling, difficulty eating or swallowing, facial swelling, weight loss, and lethargy. Since salivary gland cancer develops within the dog's mouth, a veterinarian must rule out other potential causes for these symptoms before reaching a formal diagnosis.

Diagnosing salivary gland tumors involves a multi-faceted approach. A veterinarian will typically perform a physical examination, followed by imaging techniques such as CT scans or MRIs to assess the extent of the tumor. The definitive diagnosis comes from a fine needle aspiration (FNA) and cytology, where a small needle is used to extract a sample of cells directly from the swelling for microscopic examination.

The good news is that salivary gland cancer in dogs can be treated. Treatment typically involves a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Surgical removal of the affected gland is often the primary course of action. Removing the gland decreases the flow of saliva into the swollen area and usually prevents similar capsules of saliva from forming in the area. Depending on the stage and aggressiveness of the cancer, radiation therapy and chemotherapy may be used to target any remaining cancer cells and prevent recurrence.

The prognosis for dogs with salivary gland cancer depends heavily on the stage of the cancer at diagnosis and the effectiveness of the chosen treatment plan. Early detection and aggressive treatment offer the best chance for a positive outcome. Regular veterinary check-ups, coupled with vigilant observation by owners, can help identify potential problems early on.

It is important to differentiate salivary gland tumors from other conditions that can cause similar symptoms. For example, a salivary mucocele, also known as a sialocele, is a collection of saliva that has leaked from a damaged salivary gland or salivary duct and accumulated in the tissues. This often presents as a fluctuant, painless swelling of the neck or within the oral cavity. While often inaccurately called a salivary cyst, mucoceles are lined by inflammatory tissue. The most common cause of enlarged salivary glands is a salivary mucocele, often caused by trauma to the salivary gland or duct from a wound, chewing on hard or sharp objects, or using prong collars. Surgery to remove the affected gland is also the most common treatment for a sialocele.

Other less common causes of enlarged salivary glands include sialadenosis (a neurological condition), infection, or inflammation. Mandibular lymph nodes, which can also cause swelling in the neck area, tend to be more mobile than the salivary glands when gently touched. The salivary gland feels more attached, and the mandibular lymph nodes are generally situated more rostrally (towards the front) and ventrally (underneath) the mandible, while salivary glands are positioned more to the rear and deeper in the neck.

Several factors contribute to salivary gland swellings, and these swellings result in puffiness or "swellings" in the head and neck area where the salivary glands are located. While many of these swellings are benign, it's crucial to consult with a veterinarian to determine the underlying cause and appropriate treatment.

In cases where a salivary mucocele is suspected, treatment often involves surgery to remove the affected gland, thereby decreasing the flow of saliva into the swollen area and preventing the formation of similar capsules of saliva. This is a common and effective approach for managing mucoceles.

Research has shown that salivary gland tumors are uncommon in both dogs and cats, with a reported incidence of 0.09% in dogs and 0.6% in cats. A study of 245 salivary gland biopsy specimens revealed that 42% of feline samples were neoplastic, whereas only 25% were neoplastic in dogs. Benign tumors of the salivary gland are rare in both species.

Affected animals are typically older, often over 10 years of age, and there is no specific breed or sex predilection. The cause of salivary gland tumors is generally unknown. Most cases are reported in older patients, typically between 10 and 12 years of age. Studies have not identified any specific breed or sex that is more prone to developing these tumors.

In humans, the risk of salivary gland cancer increases with age, as noted by the American Cancer Society in 2017. In 2009, the reported incidence of major salivary gland cancer in humans was 16 per 1,000,000, which is an increase from 1973 when the incidence was 10.4 per 1,000,000, as reported by Del Signore & Megwalu in 2017.

Currently, there appear to be limited contraindications for giving capromorelin in dogs with most types of cancer; however, further investigation into the interaction between capromorelin and dogs with malignant melanoma and certain types of malignant breast cancer is needed.

The symptoms of salivary gland cancer in dogs can vary, with some being more subtle than others. The most common symptoms include drooling, difficulty eating or swallowing, facial swelling, weight loss, and lethargy. These symptoms should prompt a thorough veterinary examination to rule out other potential causes and reach an accurate diagnosis.

The majority (88.8%) of salivary gland neoplasms described are of epithelial origin. Understanding the clinical features, prognostic factors, and outcomes in dogs with surgically treated salivary gland carcinoma is crucial for improving treatment strategies and patient outcomes.

Dog salivary gland cancer is a rare and aggressive neoplasm that requires prompt attention. Diagnosis typically involves a combination of physical examinations, imaging techniques like CT scans or MRIs, and ultimately a biopsy to confirm the presence of malignant cells. Surgical removal is often the primary treatment, followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy in some cases. While primary salivary gland cancer is not very common in dogs, it’s essential to be aware of the potential signs and seek veterinary care if any concerns arise.